DAN FANTE: MAN ON FIRE, Part

Two

by Ben Pleasants, guest contributor.

[May 7, 2003]

[HollywoodInvestigator.com]

Dan Fante is a short, strong fireplug of a man with close-cropped blonde

hair, the shoulders of a halfback, and a powerful stare that nails you

to your chair. He is soft spoken but like his prose, he is unflinching

and direct; no question throws him.

We are

seated for dinner in a house that once belonged to Donald Woods, a famous

actor of the 1930s. Here he once entertained Lupe Velez and Ronald

Coleman. His neighbors down the block were Rod LeRoc and Vilma Banky. The walls are filled with leather bound volumes: books, books, books. It's my wife's house and my house. I take him on the tour: show him

the Malibu tile, the great room with the books and the fireplace, the metal

shoe Wood's servant once used to polish his bootery. It's only fair,

I tell him. I was a guest in his father's house, and his mother served

me lunch and took me through the whole place.

"That

was when you had that girlfriend. The one with diabetes. The

one my father liked."

"Marlene

Sinderman. A long time ago."

Dan is

accompanied by a friend from AA. She talks about Mooch,

his Santa Monica novel, a wild and crazy look at the AA love, work, confessional

scene. I pour myself a cabernet, feeling guilty. "It's bad

enough I can't smoke a cigar anywhere. Now I can't drink in my own

house?"

They laugh

and give off their spiel about how long they've been sober.

Dan tears

into his steak, sipping water. I mention Bukowski, the long, drunken

nights out in the cold when we walked the streets of Hollywood talking

of bad poets, really bad poets, and the great John Fante.

We settle

into the living room after coffee and desert. I show him a five page

letter Bukowski wrote me about his father when we worked together at the

Free Press.

"This

part became the preface to Ask

the Dust," I say. "How would you like to hear him on tape? I've got hours of it. I was his failed biographer."

"Sure."

I play

him a long section on the crazy relationship he had with his girlfriend

Jane. How she beat him with her high heeled shoe and then went off

in a sexy dress with her latest John. It was vintage Buk: the pool

of blood he lay in covered most of the floor. We were both drunk

and laughing as he spun his magic tale on his favorite subject: the war

between men and women. I hadn't listened to it for quite a while;

both women were uncomfortable.

"Bukowski

is a man's writer," I say. "Mostly." I turn it off. Bukowski

howling at two members of AA seemed surreal. "How would you like

to hear a tape of your father?" I enquire. "You were there once when

I did them."

"I don't

remember meeting you back then."

Except

for a session at Starbucks in Santa Monica a few weeks before, the last

time I'd seen Dan Fante was at his father's funeral on May 11, 1983 at

Our Lady of Malibu Church.

"And before

that?" he asks.

"Just

once," I say. "At the place in Malibu when I was taping. 'That's

my kid,' said his father from the voice in the hall. 'He's trying

to be a writer.'"

I cart

out the box of tapes and I ask if he wants to hear a selection from the

early ones.

He nods

hesitantly. "Maybe a little," he says.

I play

a part where John Fante praised his mentor H.L. Mencken: the voice of his

father comes up softly. Dan Fante sees him in his mind's eye: the

blind man in the wheelchair seated in his living room, beneath the paintings

of his four children. As he listens to his father's voice the muscles

in his jaw begins to tighten.

I let

it play for several minutes. No one utters a word as the blood in

his face fades to pale; that tough, boiler room face with the coloring

of his mother and the features of his father. Finally he stands up. "Turn it off, please," he says, choking back a sob.

I do. The room is silent. Then he speaks. "That was not my father. My father was imperious, commanding. Sorry, Ben. I know you

really...those tapes should never be played.

The four

of us sit by the fireplace where Lupe Velez once sat as Dan composes himself. I try to make him laugh. We talk about publishers. About Stackpole

and Black Sparrow and Knopf. I show him Ferlinghetti's letter about Ask

the Dust. How I mentioned to Bukowski that City Lights was paying

him 75% of what he made on "Bukowski Stories." How he wrote back:

"I can see what Bukowski saw in this but..." How his father asked

about the advance Black Sparrow paid and how I held back my laughter. "He couldn't see me."

"You know

how much money I've made from my writing in the last two years?" says Fante. "Two-hundred-eighty-six FUCKING dollars."

We both

laugh out loud; it's comforting. How much did Homer make? Real

writing is never about the money anyway. Not for Hamsun or Celine

or Jeffers or Bukowski or Pound or Ginzberg or John Fante. It is

always the fist on the piano keys when they audience wants Mozart. Dan Fante is in that tradition.

A few

days later we talk at Starbucks on Wilshire and 26th in Santa Monica, Dan's

home away from home. This time it's theatre, playwrights, actors

and directors. Dan's favorite playwrights are Eugene O'Neill, William

Saroyan, and Tennessee Williams. Saroyan had been a friend of his

father's in Hollywood.

"Did you

know my dad was a character in Time

of Your Life? He's Willy, the pinball guy. The F on his

shirt is for Fante. It was right in the script."

We explore

the magical aspects of plays: why they last when novels fade: words alive,

not words on the page. It was Eugene O'Neill's Long

Day's Journey Into Night, that first ignited wonder in the mind of

Dan Fante.

"I began

to consider the power of words when I saw that play. It was the film

version with Ralph Richardson, Kate Hepburn and Jason Robarts Jr. There was something about the words those people were saying and their

relationships that was just magical. It was so liberating. An enormous moment of import to me because I realized the spoken word

could be a transformation. O'Neill was my first inspiration and I

remember thinking THAT is the most important thing anybody could do. Not that I thought I could do it; I think I was twelve or thirteen. His power and his anger and his honesty and his characters really hit me

between the eyes and that was the beginning for me."

I wonder

aloud if there's anything of O'Neill in Bruno Dante.

Fante

thinks a moment. "O'Neill in Bruno Dante?" He sees the connection. "Yeah. Bruno's an O'Neill character of sorts. He's my version

of O'Neill."

Writing

dialogue is Dan Fante's forte. "The clarity of the playwright for

me was more powerful than the clarity of the novel. There's something

so obvious and so assertive and so violent about dialogue that it precludes

all the trappings of literature. You can't get away with that shit

on the stage. What got me was these people could say these things

and get away with it."

Dan Fante

knows dialogue from instinct, from selling on the phone, living by his

wits, living drunk, living alone, carefully listening to what mattered.

Few novelists,

we agree have been good playwrights or vice versa. Thornton Wilder

comes to mind and Saroyan; Samuel Beckett was brilliant at both. Fante's problem with the novel is its digressions. "I like Henry

Miller, but who cares about his fucking riffs. People love that;

it turns me off."

Tennessee

Williams was a minor short story writer, a mediocre poet, and a failed

novelist, but as a playwright, "At his best, Williams was almost Shakespearian. I can sit and listen to his dialogue endlessly. To me it's like a

symphony. The other funny thing about Williams is, he wasn't a reader.

He didn't read. He couldn't get through a novel. The same problem

plagued my dad and it's plagued me to a certain extent ... Impatience. As a reader. My stuff is absent of digression. My stuff is

always linear and it's for a reason. I want people to be able to

read my books in three hours!"

In his

first produced play, "Boiler Room," performed in Los Angeles, Fante

scored a major success. The play ran for two years at The Actor's

Arts Theatre and Don Shirley hailed it under the heading OUTRAGEOUS GIFTS

IN THE SMALLEST PACKAGE. He called Fante's play a "ferociously profane

comedy about a pack of Southland Telemarkers." It was all about selling. I point out the irony of his situation: a guy who sells photocopy machines

and cars and adult film clubs on cold calls to wary businessmen can't find

an agent and makes no little money from his writing.

"I don't

confuse the two: writing and making money," he says. "I am not a

member of any literary canon or accepted mode of literature in America

and therefore I am outside … exposed to a great deal of cynicism. I don't fall into any category. People find me offensive. Everybody's

used to reading John Updike and Phillip Roth. I'm not like those

guys.

"These people [American critics] who read for a living don't

like me. The American literary establishment is so incestuous; they

have their A-list; everybody agrees what's great so if you review with

your PhD. at some Ivy league school, we know the kind of review they write

on Updike or Roth. When a Dan Fante comes along and he bites you

like a snapping turtle, they don't like it. The opposite is true

in Great Britain. In a country that has been so socially repressed,

literarily they are very advanced. They're open to new styles."

SCOTLAND

ON SUNDAY called Spitting

Off Tall Buildings "a truly great American novel." Lesley McDowell

in the Herald of London did a full page article on Mooch,

praising his literary success while singling out the key to Dan Fante's

novels: as "The link between the nostalgic need for a straightforward …

hero who does not exist, and the representation of maleness embodied in

a generation of fathers…"

"If you

read my American reviews," says Fante, "I should be pumping gas."

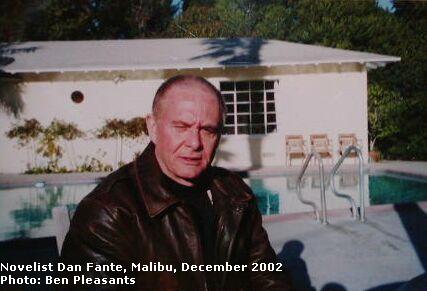

Malibu,

December 29, 2002. We are at Point Dume, in the garden of his father's

house, seated by the pool on a warm and sunny afternoon. Dan Fante

is in a relaxed mood: the Hollywood calls are coming in on Mooch and Chump

Change and the days of Dan Fante, son of John, John Jr., the John Fante

clone, are over. Derisive academicians have gone elsewhere to scoff

as the buzz on Spitting

Off Tall Buildings mounts. Malibu,

December 29, 2002. We are at Point Dume, in the garden of his father's

house, seated by the pool on a warm and sunny afternoon. Dan Fante

is in a relaxed mood: the Hollywood calls are coming in on Mooch and Chump

Change and the days of Dan Fante, son of John, John Jr., the John Fante

clone, are over. Derisive academicians have gone elsewhere to scoff

as the buzz on Spitting

Off Tall Buildings mounts.

A friend

of mine, who writes SF, points out the ironies. He read Chump

Change and found it so strong he had to put it down several times:

"It was so raw, so stripped of artifice, it stabbed me in the eye. But this one was more human. I could smell those jackets Bruno wore

in the dark when he was ushering in one of those decayed movie palaces on Fifth Avenue. And the window scenes were magic."

The tenant

who occupies the estate with her family, takes us graciously through the

house to the living room with the fireplace over which the portraits of

the four Fante children: Nick, the oldest, then Dan, Jimmy, and Vicki,

once hung. It brings back memories for us both.

We peek

into the room Dan shared with his older brother Nick when they were boys. He shakes his head and we return to the garden. Dan points out the

cactus his father planted that is now six feet high and spreading like

topsy. "That was the only thing he planted that ever grew," he laughs,

then points to a crack in the drive where he and his brother once played

basketball.

He brushes

back leaves where nothing grows but weeds. "That was where my father

put his trailer. He bought it thinking it might be a place

where he could write, but it didn't work for him, so he left it there and

it was all overgrown with vines...."

We take

our seats at the pool again and I flash off a few shots of Dan Fante facing

the front door of his boyhood home. We speak about Bruno Dante. The postmodern writing. Novels that have no counterpoint to their

point. Books that claw to the core of self; fiction without artifice,

so hot to the touch you can't put it down.

"Okay. The reason I believe my stuff has received the attention it has in Europe

and here, limitedly, is simply because it represents a new kind of American

literary edginess ... beyond Bukowski's boozy macho romances.... I'm not Irving Welsh or Jerry Stahl. It's interesting that some folks

I know in AA are shocked at my stuff. I mean at AA you hear everything

from murders to John Fante's chicken fucking yet those same people are

upset at Bruno Dante's bitterness and indiscriminate sexuality and self-mocking

rage.

"So many

writers today are excised from the plot: they write in the third person

at

arm's length. I don't do that and my father, in Ask

the Dust, didn't do that either! That book and my books are written

at a gut level. You can read Ask

the Dust today and change the price of bread and you could never tell

it was written in 1940! I'm the same. There are no riffs."

It's true. The Bruno Dante trilogy is clear and linear, a road map of Dan Fante's

life with only a few pieces missing. Spitting

Off Tall Buildings, his funniest book, is a delightful tour of his

exiled years from age 19 to 30 spent in New York. Here's Dan Fante's

introduction to driving a cab:

"I started

out rounding the block on Twelfth Avenue, then heading east on Fifty-Seventh.

The cab's odometer showed over 130,000 miles. It was an older model

Dodge, less than two years old. I found out that most fleet cabs

in New York run seven days a week, twenty hours a day.

The car's front

shocks were completely gone. The front bumper, the dash and everything

else rattled. There was a moderate shimmy at twenty miles an hour. I tested the breaks. They pulled to the right.

My first fare

hailed me from the corner of Eleventh and Forty-ninth Street. A guy

going to the Bronx.... I had little practical knowledge of how to

get around the streets by car, so I said 'I'm new. Can you direct

me?' The guy said, 'Sure. Turn left.' Three months later

I was an expert."

That's

New York as clear as it gets.

Chump

Change dumps Bruno back into the hell of LA; it's his exile returns,

a humiliating journey back to his boyhood home where he must come to terms

with his now famous dead father and his obdurate, I-told-you-so mother. The book was his first novel; it took him three years to write, and for

the reader the pain is worse than a root canal without anesthetic.

"I got

out all my rage out in Chump

Change," says Fante. "It's an angry book. It freed me from

myself."

Mooch,

his tightest novel, is Dan Fante's farewell to drink, his loss of ego,

and his final restoration of sanity, literary achievement, and social growth.

In a real

way these three novels add up to what his father only hoped to write. Dan

recalls that Full

of Life, John Fante's only commercial success, was a compromised

and romanticized look at the relationship between his father and his grandfather. Even Brotherhood

of the Grape, a much later work, never penetrated down into the level

of rage and mistrust that existed between the two men. I wonder if

the old man, as master mason, ever did any work on the Point Dume house.

"I don't

think he ever saw it," says Dan. "He died before it was built."

As we

look around the grounds, Dan confesses he has two projects burning a hole

in him these days. One is a play he wrote about his father in his

declining years. "It's called 'Don Giovanni.' It's almost done. It needs just a turn or two on the lathe from a dramaturge." The

other is a memoir of his life as a Fante. "So much of what was written

was done by writers who never knew my father. He was something, my

old man."

As we

get up to leave, he takes one last look at the grounds and laughs. "This property is surrounded by a six foot high wall. It's an acre

and a tenth. Within the perimeter and just outside are more than

three hundred fir trees. My father, with his diabolical relationship

with power tools, once, toward the end of his life, before he lost his

sight, though his vision was not very good, got himself a chain saw and

climbed that wall over there which is barely eight inches wide. He

turned on the chain saw and was just hacking away at the trees. He

had a vision of himself in chain mail hacking away at the world with a

two handed broad sword; that'll be in my book."

And so

it should.

This is

the end of Part Two. Go to Part

One.

Copyright 2003 by Ben Pleasants.

|