DAN FANTE: MAN ON FIRE, Part

One

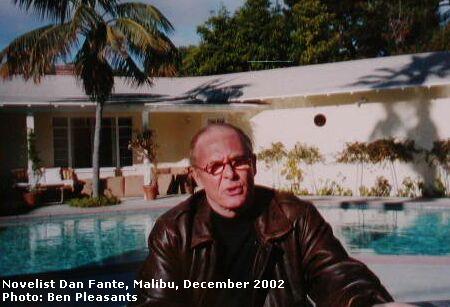

by Ben Pleasants, guest contributor.

[May 7, 2003]

[HollywoodInvestigator.com] He never wanted it that way: the two of them up there together, son and

father, Dan Fante and John Fante, squared off against each other,

contending for space on the same fiction shelf at Barnes & Noble,

Borders, and Dutton's. [HollywoodInvestigator.com] He never wanted it that way: the two of them up there together, son and

father, Dan Fante and John Fante, squared off against each other,

contending for space on the same fiction shelf at Barnes & Noble,

Borders, and Dutton's.

It's a puzzle for the reader: Chump

Change rubbing up against Dreams

from Bunker Hill; Mooch contending with Ask

the Dust; Spitting

Off Tall Buildings smack up against Wait

Until Spring, Bandini. The rage of self from father to son, passed

on over glares and unexpressed thoughts and sad regrets that cannot be

reclaimed. It's Bruno Dante and Arturo Bandini, the confessional

heroes of each colliding up there on the F shelf. And there is the

father before, John Fante's father and his father before him; and Dan Fante's

three sons and their sons. It goes on and on into oblivion.

But the

thing is, all Dan Fante ever wanted from the time he was a little boy was

the old man's love. The then not so great John Fante. His father. He'd never stopped idolizing him, looking up to him, watching

him as he worked at his machine, measuring his own steps against his father's.

Dan recalls

when he was nine, writing a story in long hand on composition paper; ten

pages or more, reading it aloud to his mother, hoping father was listening.

Instead, the old man cut him off with a rude "Enough of that shit, kid. Finish your homework." In the house of John Fante there was room

for only one writer.

Maybe

that's why Dan Fante left Malibu when he was nineteen, hit the Beat Scene

in Greenwich Village, joined an urban commune, protested the Vietnam War,

took whatever shit job he could find, and was in and out of two marriages

before he was thirty, with child support and alimony payments, ending up

a CO when all the white kids he grew up with got college draft deferments

or served in Vietnam.

When I

asked him what he thought of his parents as parents he laughed out loud

and said, "They should have traveled, or raised chickens. They never

should have had children."

The life

he lived in New York City taught him toughness, cynicism, and the hard-assed

rap of street survival. In a poem published several years later he

wrote:

Forty-one years old

checkbook balanced in the high two digits

dozens of failed jobs

and a box with photos of kids and ex-wives.

In

New York, where life was hard and money was everything, Dan Fante drank

and drank and drank down to the end of his sanity. Spitting

Off Tall Buildings vomits it all up: twelve years compressed into a

few weeks: a catalogue of crazy jobs from belt peddle to movie usher, from

night clerk to high rise window washer; life threatening jobs more out

of Kafka than Hamsun, funnier and sharper than Bukowski's Factotum,

all with the rawness and reckless truths of Celine's Journey

to the End of the Night.

That good, that relevant. The

mad landscape of desperate men and women he labored with and loved and

watched left for dead in the subway; not the New York of Seinfeld or Scrosese

or Woody Allen; but the real New York that's out there like Kafka's Castle

every day and night.

Try this

on for size. You're fifty stories above the street:

"Window washing

was where Flash became an artist. An acrobat.

First, to get

where he'd left off, he had to work himself a quarter of the way around

the outside of the building in the frozen air. He glided from window

to window with the bucket hanging from the crook of his arm. Like

a gymnast he hooked his belt onto the thick spiked nipples protruding from

the sides of each window frame and bounced effortlessly along the ledge.

In less than

a minute he'd vaulted his way to the leave off spot. Then he clamped

on and pushed backward as far as possible….His body was almost a right

angle to the building. A spider on the wall.

He began cleaning,

swaying like the sax player in the old Johnny Otis Blues Band, washing

two sets of the up and down panes at a time. For the top sections

he used a six foot wood extension.

He'd squeegee

the glass on the left, then unhook and flip himself to the next frame while

the panes were still wet, bouncing out and clamping on in one fluid motion.

Window ballet.

That's writing

worthy of Hamsun and Bukowski and even his father.

And then

there's the sad counterpoint, Dan Fante on the ropes, a little hung over,

too short for the job, leaving acres of dirty smeared glass behind as Flash

looked on laughing until he finally slipped off the ledge on the 76th floor,

dangling seven hundred feet over Manhattan as his squeegee and bucket plunged

to the street below.

"That

really happened," he said. "To me." The surfer kid from a good home

in Malibu.

So he

looked for something safer to do, driving a cab at night, his favorite

job, listening to people's problems, zooming through rain and snow and

fog and slush at 2 a.m. as bankers broke up with socialites and beat

up young mothers fled their husbands dragging along kids in pajamas.

He was

drinking more than ever, but the montage of life he drove from door to

door made him think more and more about writing. At first he wrote

poems, just for himself, and when they appeared in print, there was no

pay. "No one but Robert Frost made money writing poetry in those

days," Dan said. He knew from the beginning that writing was no way

to make money.

"I had

no illusions about wanting to be a writer. To me it was only about

money. It was only about success and it was only about power. I got that from my father. The subliminal message was: 'If you have

enough money, nobody could tell you what to do.' I managed to get

myself into the position as a telemarketer where I made so much money and

I was so successful, I could do what I wanted; but all that stopped when

I got sober. I couldn't lie over the phone anymore. It was

no longer a life and death errand."

A few

years before, to make money, he reinvented himself as CLOSER DAN, the supersalesman.

Closer Dan would show the world. Closer Dan would show his father.

Closer Dan bought muscle cars and houses in rich neighborhoods; and he

drank the best gin down to the bottom of the bottle. Closer Dan was

not a nice man; he was all about money. He was the best at what he

did and what America told him he should be, and nobody could tell him what

to do. It was a vicious circle: the gin and cocaine pumped him up

and made him into a super selling machine; but deep in the nighttime of

his soul there was a screaming kid who'd wake up in the middle of the night

and yell "enough."

His thoughts

turned back to Malibu, back to the house on Point Dume. Thoughts

of his father, long dead, came swimming into his consciousness: JOHN FANTE

the legend, his reputation growing around the world, first in France, then

Italy, then Spain, Holland, Germany, Russia; last in his own country.

With everything

gone, even his ability to sell, Dan Fante finally woke up. He gave

up booze and quit telemarketing. That was the end of the beginning. In a poem he wrote in his new book, A

Gin-Pissing-Raw-Meat-Dual-Carburator-V8-Son-of-a-Bitch from Los Angeles:

Collected Poems 1983-2002, Dan Fante recalls arriving home at his mother's

house...

with all I own in a plastic bag …

Mom opened the door

and smiled when she saw me …

and I went off to the spare bedroom

sad for my old man's fading ghost…

Without

drink, at 46, unemployed and disgusted with life, he was forced to attend

AA. Forced by the courts. At first it meant nothing;

just another scam. He sat and listened to the others share their

horror stories; cynical, angry, not wanting to be there, unable to admit

his rage, his failures: the demolished marriages and busted families, the

DUIs, the jail time and the insatiable curiosity of the IRS.

He recalls

one AA meeting where a member was given a birthday cake for being sober

twenty years and Closer Dan opened up on the whole assemblage spraying

venom. "I've never heard such bullshit and I don't believe a word

of it," he shouted. But the AA faithful had heard it before and they

listened to his rage with empathy. He was speaking their language,

but with genius, with magical fires.

"All drunks

are poets in some ways," a famous friend once told me. "They lay

out in the freezing air at night and see the moon in a way the rest cannot."

"You should

write it down," his sponsor told him. "Lots of drunks are writers. Write it all out. It's the best way to see what's inside." That's how it started: poems and plays and stories and novels. Fante

went three times a week to AA and Dan the Closer, Dan the Pitchman, slowly

began to die.

As his

head began to clear, things came back to him: the first teacher who ever

told him he should become a writer; Mrs. Ahern the names of faces of the

kids he grew up with in Malibu; the surfing revolution of the Sixties.

They were

just thoughts at first, but he wrote them down on scraps of paper and then

in notebooks. And it got easier. The talk and the writing came

together. He had always been a good talker, a convincer, a pitchman. The thoughts became sentences, then paragraphs, then pages of what he'd

kept trapped inside himself for more than thirty years; it all came spilling

out like poison: the all night drunks, the DUIs, the love-hate marriages,

the selling of stuff, the selling of self, the selling of love.

At first

it was just one title,Chump

Change, the opening novel in the Bruno Dante trilogy. John Martin,

John Fante's publisher at Black Sparrow, was the first editor to read it. "He kicked it right back to me, saying it was too close to what he had. There was an implication it wasn't very good. He's since eaten his

words and told Al Berlinski (editor of Sun Dog Press who first published Chump

Change in America), "he is 'pleased' with my success. I've inquired

about other stuff -- my poems -- by email; but he never even returned the

query."

When Chump

Change arrived in print on her doorstep, Joyce Fante, Dan's mother,

wrote John Martin, his father's publisher at Black Sparrow, and Stephen

Cooper, author of Full

of Life, the standard Fante biography, excoriating the novel.

"She would

in no way have my 'garbage' associated with the name of John Fante." That was a shock.

Chump

Change has been hailed in Europe as "absolutely tremendous; as funny,

sad, angry and human as it gets." (Charlie Hill, Birmingham Post). Anthony Reynolds of London's Beat Scene wrote: "It's grotesquely readable,

full of quiet horror and broad melancholy. It'd make a good film."

The French journal Soud Ouest called it "sublime."

The novel

was published first in Paris; no editor in America would read it until

it was translated into French and published by Fixot Seghers. It

was Jean Claude Zylberstein, John Fante's champion in France, who discovered

the book, passing it on to Robert Laffont, who accepted the book two weeks

after he received it .

So it

goes in America for father and son.

There

is an amazing tribute to his father in Chump

Change, but his son notes without bitterness, "Chump

Change never got a real American review."

Joyce

Fante has since come around with praise, calling his new book of poetry

"more akin to surgery or the body shop than to the techniques of music

and painting … Pain and self-mocking humor are the writer's tools…."

But for

Dan Fante it's always been about his father, the writer he could never

please, the man he loved and emulated and still hungers for; the tough

John Fante who taught him not to be a writer. "The fact that he was

a writer probably dissuaded me from wanting to be a writer. The question

is often asked: 'What is it like to be the son of a successful writer?'

"My father

wasn't a successful writer when I was a kid! He wasn't any kind of

a literary model. He was a screenwriter and I knew he was terrific

at that. Only after he died, when I'd lost everything and you get

to the place where you can only see sky.... I had this passion, this

love for my father that transcended my relationship with him. And...

It was

the late 80's. He was just beginning to get some notoriety.

Some of

his stuff had been republished and people were beginning to talk about

him. "Then I really wanted to write a book that would point people to my father. That was the reason I wrote Chump

Change. It was for my father. It was a love letter. All these jerk-offs who never met him were writing stuff about him as though

they'd known him all his life and they got so much of it wrong."

This is

the end of Part One. Go to Part

Two.

Copyright 2003 by Ben Pleasants.

|