|

Home

About

Us

Bookstore

Links

Blog

Archive

Books

Cinema

Fine Arts

Horror

Media & Copyright

Music

Public Square

Television

Theater

War & Peace

Affilates

Horror Film Aesthetics

Horror Film Festivals

Horror Film Reviews

Tabloid Witch Awards

Weekly Universe

Archives

|

GENE H. BELL-VILLADA ON NABOKOV, AYN RAND, AND THE LIBERTARIAN MIND

by Thomas M. Sipos, managing editor [July 5, 2014]

[HollywoodInvestigator.com] Gene H. Bell-Villada is a professor of romance languages at Williams College, having earned his doctorate in the field at Harvard. He's written or edited eleven books, including Art for Art's Sake & Literary Life, a finalist for the 1997 National Book Critics Circle Award, and The Pianist Who Liked Ayn Rand, a collection of essays and short fiction, including a novella that satirizes the Ayn Rand cult phenomenon. [HollywoodInvestigator.com] Gene H. Bell-Villada is a professor of romance languages at Williams College, having earned his doctorate in the field at Harvard. He's written or edited eleven books, including Art for Art's Sake & Literary Life, a finalist for the 1997 National Book Critics Circle Award, and The Pianist Who Liked Ayn Rand, a collection of essays and short fiction, including a novella that satirizes the Ayn Rand cult phenomenon.

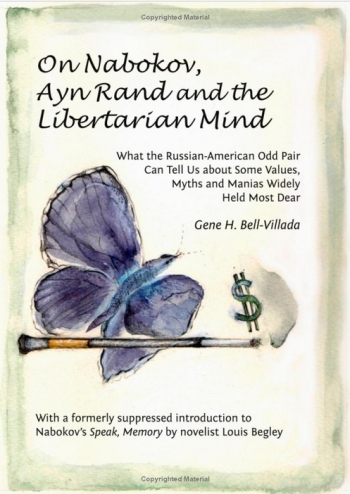

Bell-Villada's latest book, On Nabokov, Ayn Rand and the Libertarian Mind, returns to Rand, finding parallels between her life and philosophy, and that of Vladimir Nabokov.

Rand is widely known for her influence on libertarian philosophy, but why should libertarians be interested in Nabokov?

"Anyone involved with literature, ideas, or culture should be interested in Nabokov," said Bell-Villada to the Hollywood Investigator. "He wrote two of the most original, innovative, influential, comical, and in some ways beautiful American novels of the second half of the 20th century: Lolita and Pale Fire. The rest of his writing is quite uneven, and he even wrote some bad books. But that is another matter.

"Nabokov was not a thinker. He loathed thinkers. He had no specific ideas about social organization, and I doubt he even knew what 'the market' signified as an intellectual construct. Yet his political ideas are essentially an unreconstructed, unmodified 19th century liberalism. "Nabokov was not a thinker. He loathed thinkers. He had no specific ideas about social organization, and I doubt he even knew what 'the market' signified as an intellectual construct. Yet his political ideas are essentially an unreconstructed, unmodified 19th century liberalism.

"In many ways, American libertarianism is a revival of 19th century liberalism, adapted to modern realities such as the warfare state, gay rights, drugs, and even feminism (positions which libertarians pretty much appropriated from the '60s left and even from the Old Left). Not accidentally, in Western Europe and Latin America, libertario/libertaire is a synonym for anarchist, whereas libertarians are known as neo-liberals.

"Moreover, there is the matter of individualism vs. determinism. To quote my chapter 13, 'On Their Respective Legacies':

"Each of these writers [i.e. Nabokov and Rand] believed in an intrinsic, aprioristic, totally self-fashioned individual autonomy, and so both balked at the slightest hint of determinism and denied the very existence of society as an entity with dynamics of its own. Only individual actions and values mattered, in their view. Above all, Nabokov prized absolute freedom of art and the free inventiveness of genius; Rand gave sole credence to absolute freedom of enterprise and to inventors of genius."

"Nabokov's absolute aestheticism is in many ways a variant of libertarianism, applied to literature. Just as Rand and libertarianism reject the social ethic and what Hayek called 'the mirage of social justice,' Nabokov scorns the social aesthetic and the mingling of literary art with issues of social justice.

"Here is a passage from my book's 10th chapter, 'On Politics and Society':

"Nabokov’s spokesman and alter ego in The Gift, his poet-aesthete Count Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev, does speculate on what he calls 'my kingdom, where everyone keeps to himself, and there is no equality and no authorities' (G, 370).

"This is about as 'libertarian' a stance as one will find in Nabokov, and it is of a piece with the totality of his world-view. Indeed, Count Fyodor’s general outlook much resembles that expressed by John Galt in his mammoth radio address, where at one point Rand's hero declaims: 'Do you ask what moral obligation I owe to my fellow man? None -- except the obligation I owe to myself…' (948). For just as Rand is concerned solely with the rights of superior architects, inventors, and businessmen to achieve greatness and wealth, and the devil take the rest, Nabokov cares exclusively about the rights of exquisite literary artists to write great art, and the devil take the rest."

"So while Nabokov's writings don't relate to the development of libertarian philosophy," says Bell-Villada, "his essential worldview and aesthetic were libertarian. "So while Nabokov's writings don't relate to the development of libertarian philosophy," says Bell-Villada, "his essential worldview and aesthetic were libertarian.

"Also, I wrote this book not so much for a libertarian audience as for a broader readership, one whose members would like to inform themselves about these two authors and the larger topic of libertarianism, the latter of which is a growing force in the U.S."

But why a book about both Rand and Nabokov? Other than their both being Russian writers, do their lives and works intersect in any meaningful way?

"Obviously they are diametrically different writers," says Bell-Villada. "And yet their life trajectories show certain parallels.

"Both fled Russia and the Bolshevik regime, which they hated in principle -- not just because of its violence and dictatorship, but because of what the regime stood for. Both began writing about Russian topics. Rand set We the Living in Soviet Leningrad/ Petersburg, while Nabokov's earlier novels deal with the Russian emigré community in Berlin.

"Once in the U.S., they found themselves as American writers within a specific American ideological setting. Rand inserted herself in the world of pro-business intellectuals and publicists. Nabokov flourished in the American academic enclaves where ideas of 'art for art's sake' had become thoroughly implanted and in which he found an intellectual home.

"In sum, starting with The Fountainhead and Lolita, each became American authors and, in their writings, put Russian issues behind them.

"Yet their Russianness is very much a part of their outlook. They were both as dogmatic and absolute as was the Bolshevik regime. Moreover, they brought to their fiction (to his earlier ones in the case of Nabokov) a Russian obsession with ideas.

"Here's a passage from my chapter 11, 'On Their Russian Side':

"Both Rand and Nabokov, however, are Russian in profound and sometimes hidden ways. As writers, for starters, they stand squarely within their country’s tradition of the novel of ideas. It is a recognized feature of nineteenth-century Russian literature that its authors strove to integrate general ideas (and perhaps even ideologies) into their plots and narratives. Faced as they were with the backward condition of their country -- economic, political, intellectual, legal -- and the various political schemes to deal with that condition, novelists under Tsarism saw those diverse plans as part of the human landscape and purposely gave them flesh, blood, and voice...

"The Russian novelists, then, while not being 'thinkers' in the strictest sense of the word, certainly channeled their narrative art into representing thought and thinkers. In so doing, they oftentimes fell into what the noted intellectual historian Aileen Kelly describes as the 'habit of taking ideas and concepts to their most extreme, even absurd conclusions.' In their 'search for absolutes' as well as in their 'radical denial of absolutes,' Kelly further argues, the Russian intelligentsia 'embodied the thirst for absolutes in a pathologically exaggerated form.' Kelly’s words well characterize our Russian odd pair -- Rand in her absolute advocacy of capitalism and her total hatred of social altruism (both in theory and in actuality), Nabokov in his absolute aestheticism and equally absolute denial of 'the social' (both in lit. and crit., and in the world)."

"Here I should explain," Bell-Villada continues, "something scarcely known to those who aren't acquainted with Nabokov's earlier works. Two of his novels, The Gift and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, are novels of ideas, publicist works. The idea being publicized in them is aestheticism, art for art's sake. Art all pure, at the expense of the social aesthetic, the latter being portrayed in the most negative terms possible. (Many of Nabokov's ardent fans reject this characterization, but there is no honest way one can disregard this phase of his career.)

"Also, like Rand in Anthem, Nabokov penned two works of dystopian fiction, depicting what he saw as collectivist tyranny: Invitation to a Beheading and Bend Sinister. And, as with Anthem, they are rather limited, not at all major works in his canon."

What about Rand? Bell-Villada's novella, The Pianist Who Liked Ayn Rand, demonstrates that he's long been well studied in the cultish attraction Rand holds for some fans. And now another book about Rand. What is it about Rand that he considers so important or interesting as to merit two works? What about Rand? Bell-Villada's novella, The Pianist Who Liked Ayn Rand, demonstrates that he's long been well studied in the cultish attraction Rand holds for some fans. And now another book about Rand. What is it about Rand that he considers so important or interesting as to merit two works?

"Ayn Rand is probably the most influential fiction writer in the United States today," Bell-Villada replies. "Polls have repeatedly demonstrated this. Her ideas have become common currency within the conservative movement. One sees signs tacked onto telephone poles or being carried at Tea Party rallies that say, 'Who Is John Galt?' The list of business leaders and politicians who believe in Rand, or at least think like her, is long. In Senator. Ted Cruz's 23-hour filibuster against the Affordable Care Act, among the things he read from was Atlas Shrugged.

"Rand is scarcely known outside of the U.S. In this country, though, she taps into the individualist strain that is so much a part of American culture. She gave a voice to those pro-business circles who not only hated communism but were against social-democratic solutions, the New Deal, or any government intervention in the economy. Few adolescents, however intelligent they may be, can read Milton Friedman or Friedrich von Hayek.

"Rand gave flesh and blood to the ideal of a society guided solely by market principles. You'll find no sex, no romance, no mystery, no human-interest elements in the likes of Friedman or Hayek. Rand, by contrast, brought these components to her philosophy and her narratives. And of course she expressed them in simple -- not to mention simplistic -- ways that teenagers and semi-educated readers could respond to.

"Since few non-conservative readers read much Rand, I wrote the book in great measure for them, as a way to initiate them into her writings. The book is an introduction to its subject matter, much as my volumes on Latin American authors are."

Although many have written about the lives of Rand and Nabokov, Bell-Villada believes he's still brought original material to the table.

"In the 1990s Random House commissioned novelist Louis Begley to write an introduction to a new edition of Nabokov's Speak, Memory. Begley wrote it, and it went into galleys. Then Nabokov's son Dmitri got hold of it. He objected to Begley's rather mild criticism of Nabokov's indifference to the Nazi regime in the novelist's recollections of Berlin in the 1930s. "In the 1990s Random House commissioned novelist Louis Begley to write an introduction to a new edition of Nabokov's Speak, Memory. Begley wrote it, and it went into galleys. Then Nabokov's son Dmitri got hold of it. He objected to Begley's rather mild criticism of Nabokov's indifference to the Nazi regime in the novelist's recollections of Berlin in the 1930s.

"Dmitri demanded changes. Begley refused. So Dmitri had the introduction scratched. At a conference on Nabokov at Cornell in 1999, Dmitri publicly bragged, 'The introduction did not appear.'

"When I found out about this incident, I tracked Mr. Begley and asked if I could use the essay as an appendix to my book. He got hold of the galley proofs from the Boston University Archives and sent it to me, giving me permission to use it. His intro to Speak, Memory found a home in my volume, as an appendix.

"I should observe that I enjoy a good intellectual relationship with certain libertarian scholars -- Chris Matthew Sciabarra, Mimi Reisel Gladstein, Shoshana Milgram. I've even published in Sciabarra's magazine, the Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. One thing is libertarianism as an idea to be discussed and bandied about, another is the 'vulgar libertarianism' (by analogy with 'vulgar Marxism') that I see taking hold in this country."

Finally, Bell-Villada believes that his own personal background influenced his own interest in Rand.

"My background is very complicated," he says. "I was born in Haiti, and grew up in Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Venezuela. My father was a WASP adventurer from Kansas. My mother was Chinese-Filipina from Hawaii, where he originally met her, and whence he spirited her off to the Caribbean, to make money.

"My father was an obsessive entrepreneur who could have walked out of the pages of a Rand novel. His sole focus was making money, at the expense of all else. He was totally indifferent to his family and showed virtually no interest in his children and their development. He exploited my mother as a free secretary, then dumped her for a blond Cuban. He came close to destroying all of us, including my two siblings. My mom even attempted suicide when things were at their worst.

"Here is a relevant excerpt from my book (which contains quite a bit of autobiography):

"In his role as a father, I have no memory of his playing, romping, biking, or chatting with my brother and me, or of him teaching us, or doing yard work with us, or taking us to cultural or sporting events. I have only a recollection or two of his going for family strolls with us. In Puerto Rico and later in Cuba, both my brother and I were good students who got excellent grades, making Honor Roll numerous times. Yet my father never offered any congratulations for our achievements. In fact, I cannot recall his demonstrating any pride or pleasure in his children at all. And of course he never refers to us in his many letters. Not believing that the environment shapes a human being, he took next to no interest in creating a suitable environment for his offspring...

"My father, then, shared with Ayn Rand, and with her business heroes Hank Rearden, Dagny Taggart, and John Galt, the ideal of a selfish pursuit of individual wealth, together with a studied indifference toward others and a concomitant lack of interest in nurturing or loving his own blood-kin. At home and elsewhere, he lived by Galt’s dictum: 'Do you ask what moral obligation I owe to my fellow man? None -- except the obligation I owe to myself.' If one adds the words 'and family' after 'fellow man,' the Galtian statement of principles fits my male progenitor perfectly. And again, like Rand herself receiving crucial help from all sorts of people throughout her life, while asserting apodictically that no one had helped her along the way, my father too claimed to be 'self-made' and to have earned everything, in his familiar words, 'from the sweat of my brow.'

"In many ways, when I write about Rand, I'm writing about my father. Like my previous memoir -- Overseas American: Growing Up Gringo in the Tropics -- this book is a catharsis, an exorcism. I am exorcising the Randian ghost that was my evil and destructive dad. "In many ways, when I write about Rand, I'm writing about my father. Like my previous memoir -- Overseas American: Growing Up Gringo in the Tropics -- this book is a catharsis, an exorcism. I am exorcising the Randian ghost that was my evil and destructive dad.

"I believe the above should help explain why I choose to write about Ayn Rand! She is a horrible writer, but one who nonetheless represents powerful forces in American life, my father being a specimen thereof."

|